Blade profiles is one of those subjects to which entire web sites could be dedicated and somebody would still find something that wasn’t covered adequately, or a case where something didn’t apply. Nonetheless, it’s useful to understand what’s being talked about when there’s a reference to blade profiles and rocker radius (sometimes written as Radius of Rocker, or RoR in a similar way to Radius of Hollow (ROH)). Hopefully I can make some sense of the topic without getting too dragged down into the many, many variables involved.

Blade Profiles

The phrase blade profile

refers to the shape of the blade surface (that is, the bit that touches the ice) as viewed from the side. I’m only one sentence in, but I already have to add a caveat that some manufacturers have also created products which change the profile of the width of the blade along its length (for example, John Wilson Parabolic blades, or some of the tapered blades which are thicker at the front and narrower at the back). For the purposes of this page however, we will ignore this complication and concentrate on the side profile of the blade.

Unsurprisingly there is no “one size fits all”

for blade shapes, and over the years manufacturers have experimented with different curves and toe pick designs with varying degrees of success. In the end, though, many current blades seem to try to emulate some classic John Wilson blade designs such as the Gold Seal and Pattern 99, which are ubiquitous competition-level blades.

Anatomy Of A Blade

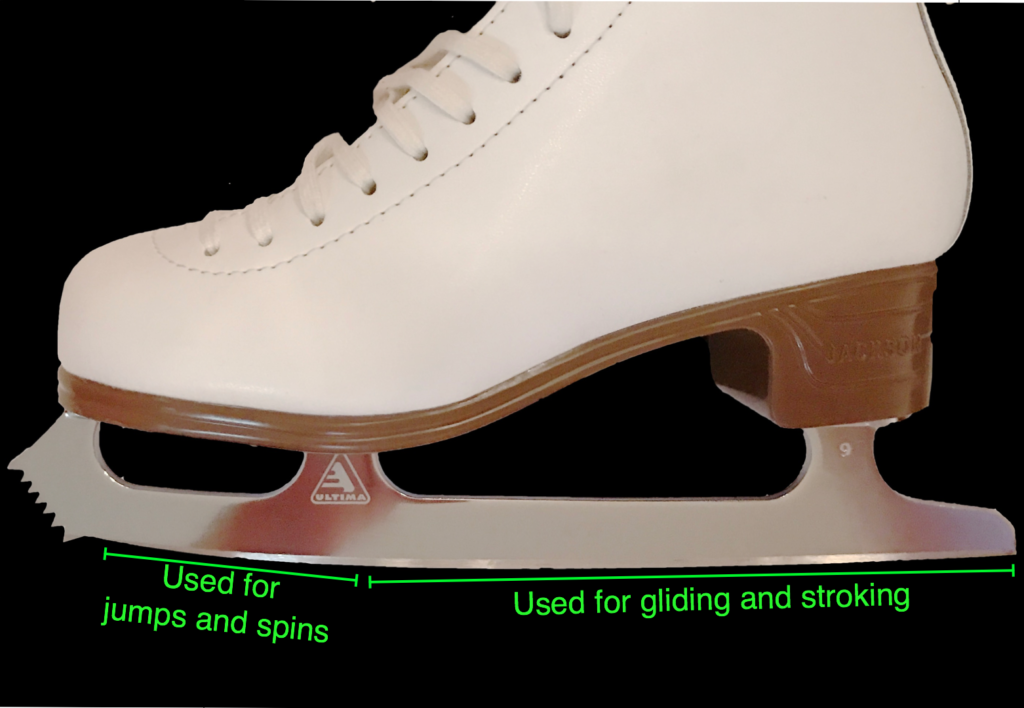

Figure skate blades are made up of three main functional sections, and understanding what each part of the blade does will help with the further explanations below.

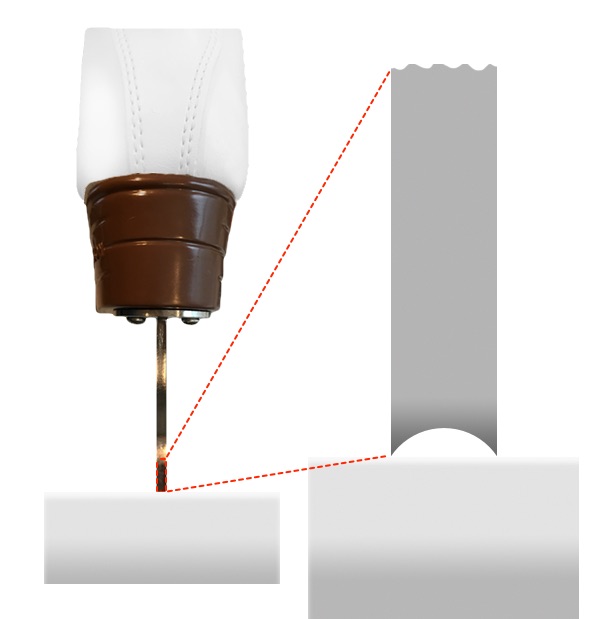

The diagram above shows the two parts of the blade which are used for movement; the third part are the toe picks on the front. I am, by the way, ignoring the lethal weapons (toe picks) on the front of the blade for the moment. While they—and their relationship to the blade—are important, they won’t help this discussion any.

It’s important to understand that the two labeled parts of the blade are used for different moves. When gliding or stroking on the ice, the skater uses the rear part of the skate (the rocker). When performing jumps and spins, however, the skater moves their weight forward to use the front part of the blade (sometimes called the “spin rocker”). This is why the tapered blades I mentioned above are thicker at the front; to support the jumps and spins.

Rocker Radius

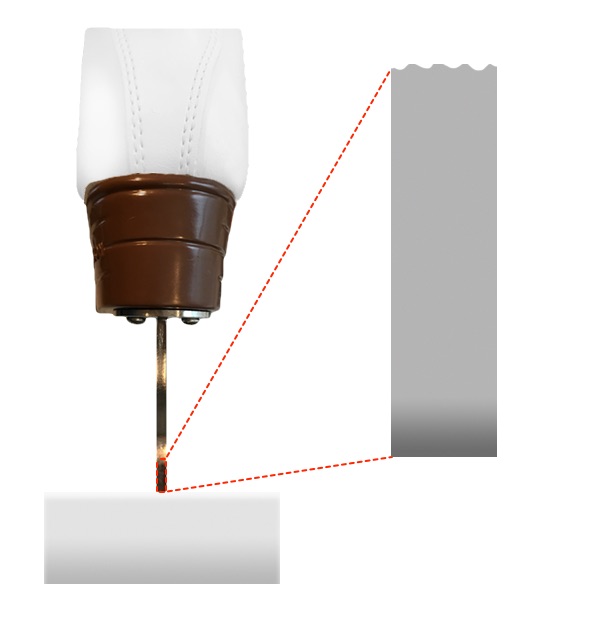

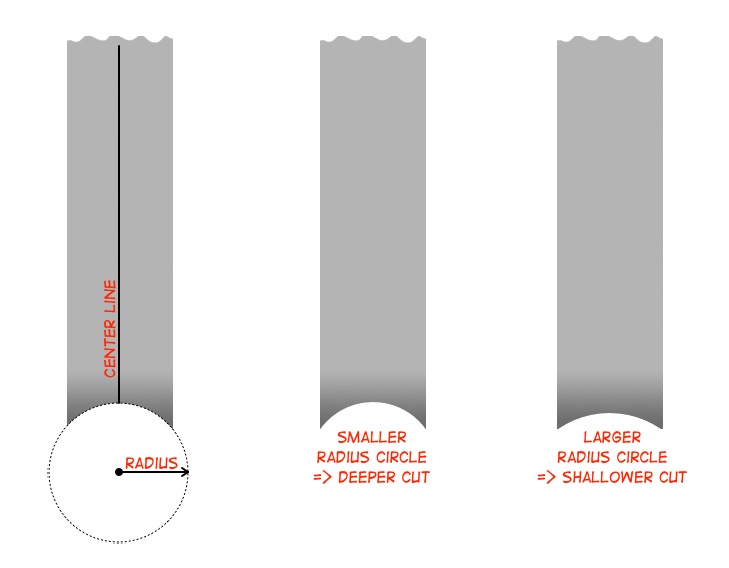

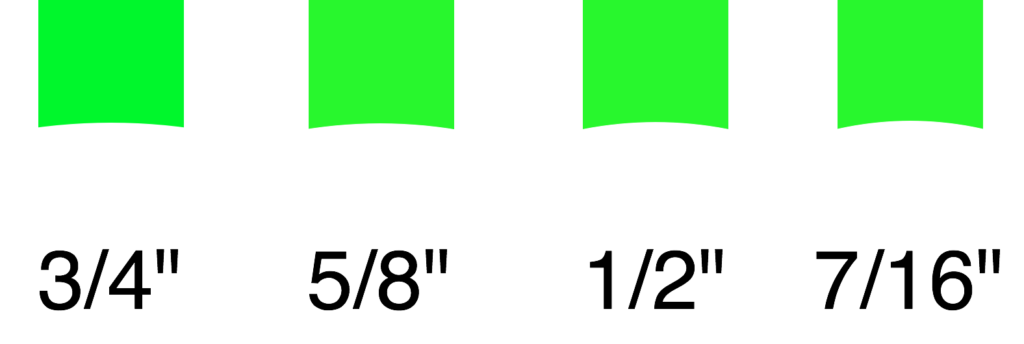

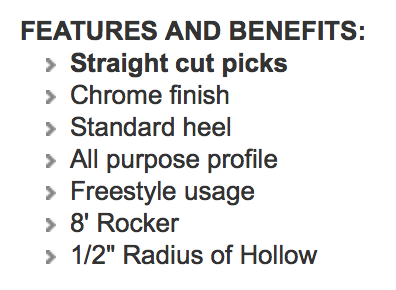

The shape of the blade profile for figure skates is usually quoted in feet, and as with Radius of Hollow, the idea is that if one were to draw a circle with that radius, the shape of the bottom of the blade would follow an arc of that circle. If that’s confusing—and it probably is—let’s make it clearer by using my daughter’s Jackson skates as an example. Her skates have the Mirage blade on them, and Jackson’s website has this specification:

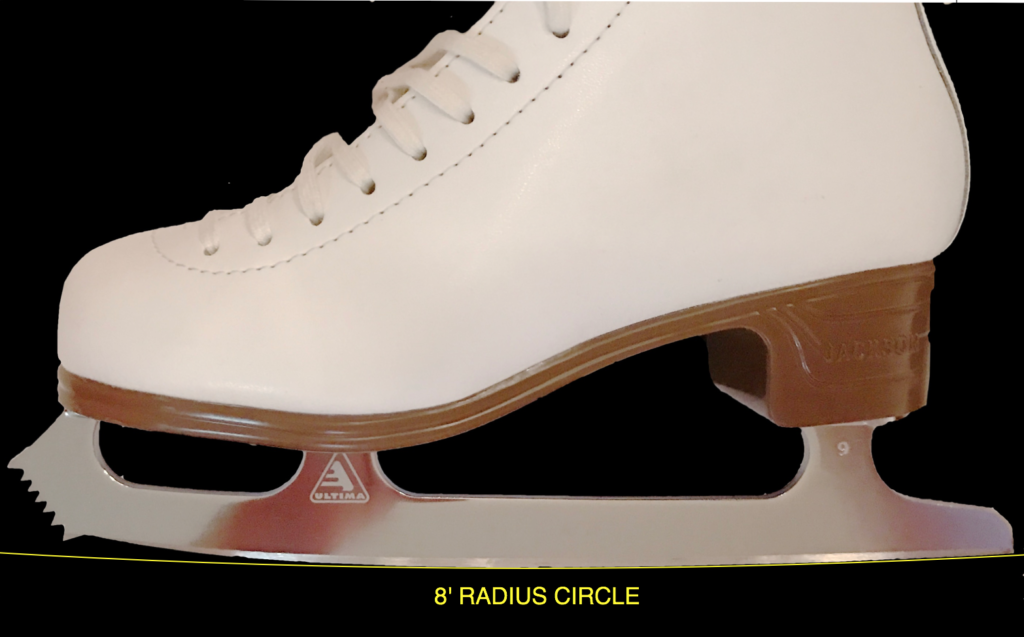

Based on the information above, the Mirage has an 8′ rocker radius. To illustrate this, I took the skate image into a drawing program and scaled it to represent its actual measured size. I then created an 8′ radius (16′ diameter) circle and overlaid it so that the circle’s arc could be matched against the blade. This is the result, and the thin yellow line is a small arc from that huge circle:

What should be obvious here is that while much of the blade aligns with the stated rocker radius, not all of it does. The rocker radius really refers to the rear part of the blade that’s used for gliding and stroking. The section of the blade used for jumps and spins is clearly not using a circle of the same radius.

What difference does the rocker radius make? Well, a larger radius means a flatter blade, which means more of the blade will contact the ice at any one time. This may make the blades feel a little more stable, although they may be marginally less maneuverable on the ice. Conversely a smaller radius means a smaller contact area, and skaters seem to report more instability especially if they were used to a larger radius rocker previously. Choosing an appropriate rocker radius is definitely an area where talking to your skate tech and coach is important. However, as you’ll see below, the rocker radius alone does not define everything about the blade’s behavior.

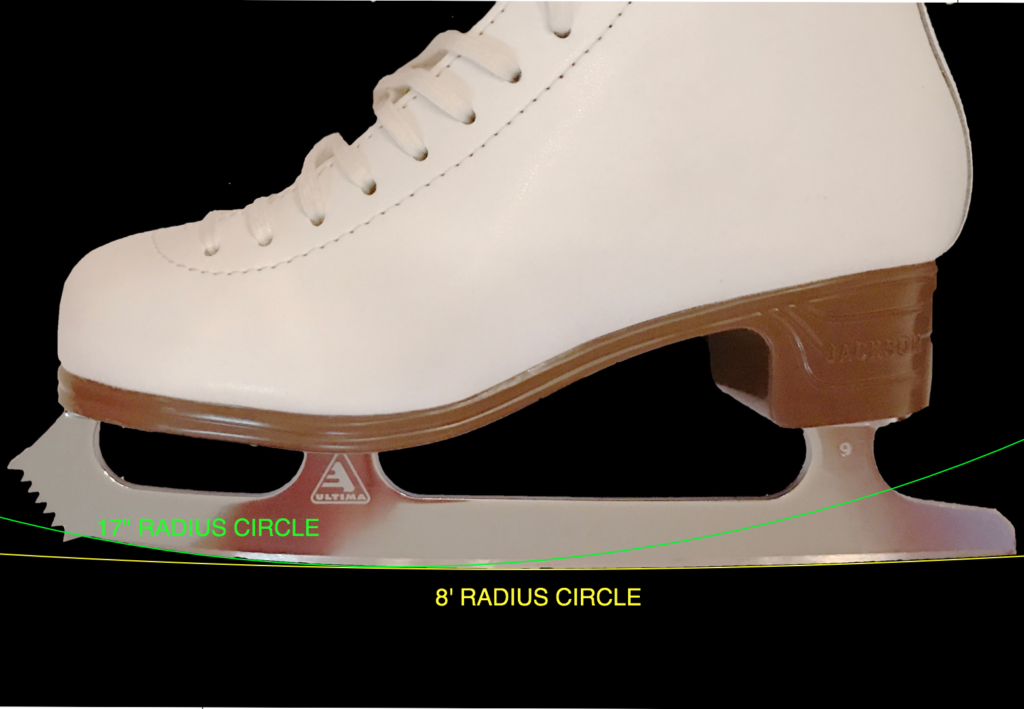

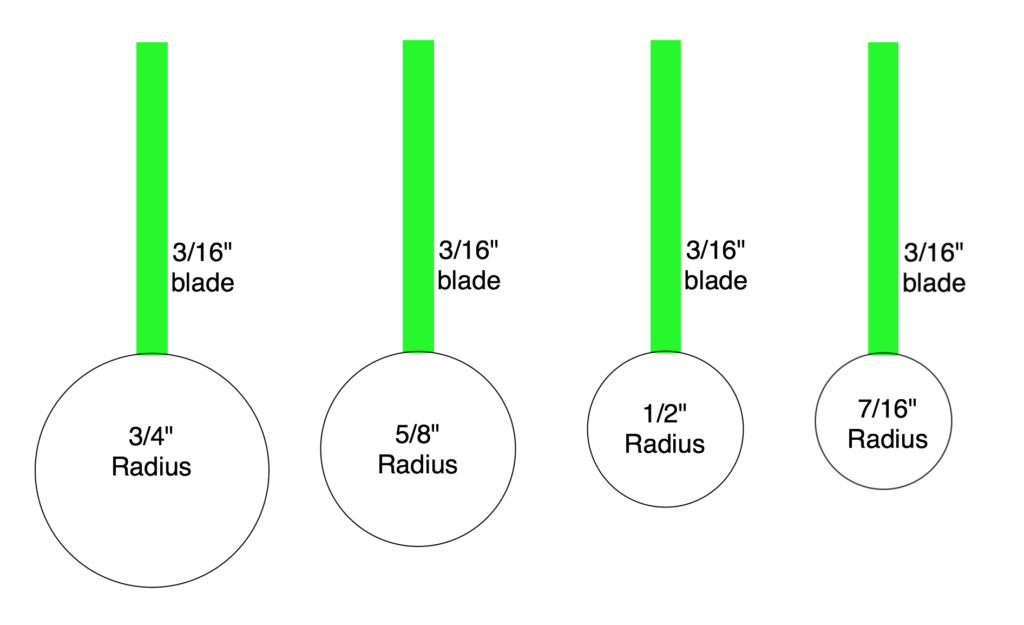

Two and Three Radius Blades

Figure skating blades do not in fact use a single radius, despite that being what’s quoted on the literature; they typically use two or even three radiuses along the blade. The largest radius is reserved for the rear section, and the front jump/spin section will normally be cut either from one other radius, or split into cuts along two different radius arcs. Looking at the Jackson Mirage blade again, the front section appears to be cut using somewhere around a 17″ radius. I have overlaid a green circle on the previous image demonstrating this much sharper arc as seen at the front of the skate:

It’s interesting to me that the only radius quoted for almost every blade is the main rocker radius rather than the front radius (or radiuses), because it seems to me that for a figure skater the properties of the area on which they perform jumps and spins might be far more important to them, or at least might have more impact on the skating performance. Maybe I’m wrong. What do you think?

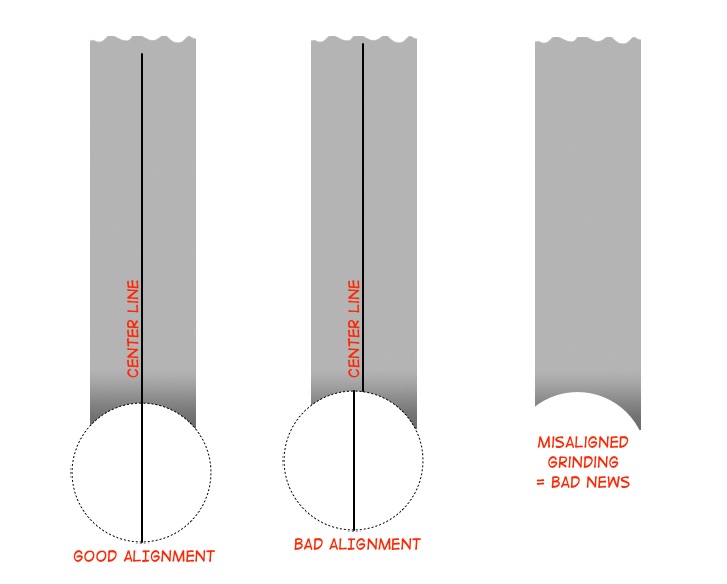

Accuracy of Sharpening

Given that the exact curvature of each make and model of blade are part of the blade’s characteristics, finding a skate tech / blade sharpener who can accurately and consistently grind the right profile on to the blades is really important. In fact, this will probably become a recurring theme on this blog when it comes to skate maintenance: find a great skate tech (word of mouth is usually a good way), make friends with them, grab hold of them and never let go! You need to be able to trust that when your skates are sharpened, they’re going to come back correctly sharpened, the same way, every time. The corollary to this is that taking your skates to be sharpened by a different person or at a different place each time is a bad idea.

Hopefully if this was previously a confusing topic, this helped shed some light on the subject.